Literature is the art of written works, and is not bound to published sources (although, under circumstances unpublished sources can be exempt). The two major classification of literature are poetry and prose. Others exclude all genres such as romance, crime and mystery, science fiction, horror and fantasy.

The theory of dominant group with respect to literature falls into at least two situations: a dominant group of literature or a dominant group associated with literature.

Dominant group

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Dominant group

Examples from primary sources are to be used to prove or disprove each hypothesis. These can be collected per subject or in general.

- Accident hypothesis: dominant group is an accident of whatever processes are operating.

Main resource: Dominant group/Accident laboratory

- Artifact hypothesis: dominant group may be an artifact of human endeavor or may have preceded humanity.

Main resource: Dominant group/Artifact laboratory

- Association hypothesis: dominant group is associated in some way with the original research.

Main resource: Dominant group/Association laboratory

- Bad group hypothesis: dominant group is the group that engages in discrimination, abuse, punishment, and additional criminal activity against other groups. It often has an unfair advantage and uses it to express monopolistic practices.

Main resource: Dominant group/Bad group laboratory

- Control group hypothesis: there is a control group that can be used to study dominant group.

- Entity hypothesis: dominant group is an entity within each field where a primary author of original research uses the term.

- Evolution hypothesis: dominant group is a product of evolutionary processes, such groups are the evolutionary process, produce evolutionary processes, or are independent of evolutionary processes.

- Identifier hypothesis: dominant group is an identifier used by primary source authors of original research to identify an observation in the process of analysis.

- Importance hypothesis: dominant group signifies original research results that usually need to be explained by theory and interpretation of experiments.

- Indicator hypothesis: dominant group may be an indicator of something as yet not understood by the primary author of original research.

- Influence hypothesis: dominant group is included in a primary source article containing original research to indicate influence or an influential phenomenon.

- Interest hypothesis: dominant group is a theoretical entity used by scholarly authors of primary sources for phenomena of interest.

- Metadefinition hypothesis: all uses of dominant group by all primary source authors of original research are included in the metadefinition for dominant group.

- Null hypothesis: there is no significant or special meaning of dominant group in any sentence or figure caption in any refereed journal article.

- Object hypothesis: dominant group is an object within each field where a primary author of original research uses the term.

Main resource: Null hypothesis

- Obvious hypothesis: the only meaning of dominant group is the one found in Mosby’s Medical Dictionary.

- Original research hypothesis: dominant group is included in a primary source article by the author to indicate that the article contains original research.

- Primordial hypothesis: dominant group is a primordial concept inherent to humans such that every language or other form of communication no matter how old or whether extinct, on the verge of extinction, or not, has at least a synonym for dominant group.

- Purpose hypothesis: dominant group is written into articles by authors for a purpose.

- Regional hypothesis: dominant group, when it occurs, is only a manifestation of the limitations within a region. Variation of those limitations may result in the loss of a dominant group with the eventual appearance of a new one or none at all.

- Source hypothesis: dominant group is a source within each field where a primary author of original research uses the term.

- Term hypothesis: dominant group is a significant term that may require a ‘rigorous definition’ or application and verification of an empirical definition.

Literature

[edit | edit source]

Def. “the body of [all] written work”[1] is called literature.

The theory of literature involves methods of studying and investigating literature, its “nature and function”; “literary theory, criticism, and history; and general, comparative, and national literature.”[2]

Def. “[t]he theory or the philosophy of the interpretation of literature and literary criticism”[3] is called literary theory.

Writings

[edit | edit source]

His bringing “writing center practice into line with the authorized knowledge about writing, and his widely followed stricture that tutors are to support the classroom teacher’s position completely is clear evidence of how writing centers do not escape domination. Yet one of the benefits of being excluded from the dominant group is that in this position one has less to protect and less to lose.”[4]

Abstractions

[edit | edit source]

Def.

- a “separation from worldly objects”,[5]

- “the withdrawal from one’s senses”,[6]

- the “act of focusing on one characteristic of an object rather than the object as a whole group of characteristics;[7] the act of separating said qualities from the object or ideas”,[6]

- the “act of comparing commonality between distinct objects and organizing using those similarities;[7] the act of generalizing characteristics; the product of said generalization”,[6]

- an “idea of an unrealistic or visionary nature”,[6] or

- any “generalization technique that ignores or hides details to capture some kind of commonality between different instances for the purpose of controlling the intellectual complexity of engineered systems, particularly software systems”[8]

is called an abstraction.

The image on the right is an example of the literature of abstraction.

Adventures

[edit | edit source]

Adventure fiction is a genre of fiction in which an adventure, an exciting undertaking involving risk and physical danger, forms the main storyline.

“An adventure is an event or series of events that happens outside the course of the protagonist’s ordinary life, usually accompanied by danger, often by physical action. Adventure stories almost always move quickly, and the pace of the plot is at least as important as characterization, setting and other elements of a creative work.”[9]

Comedies

[edit | edit source]

“Thus, the use of stereotypes in popular fictional forms such as situation comedies may be rather less unambiguously a reflection of dominant group views than Dyer suggests.”[10]

“Mean scores for number of Smile and Laughter responses in telic and paratelic state-dominant groups throughout six successive 100 sec periods during exposure to comedy.”[11]

“Yet the situation of women is more complex because of their close involvement with members of the dominant group, which has blurred the boundaries between “us” and “them.””[12]

Comparative literature

[edit | edit source]

“Without doubt, multiculturalism is preferable to the monoculturalist oppression of minorities by the dominant group.”[13]

Criticism

[edit | edit source]

Def. “[t]he study, discussion, evaluation, and interpretation of literature”[14] is called literary criticism.

“But my point is that one constant within this struggle remains: that an oppositional culture of non-dominant groups has to define itself against the practices and ideology of the dominant group (or groups), and this inevitably has consequences for form. Indeed, only a very unsophisticated literary criticism could conceive of form and content as distinct entities.”[15]

Compositions

[edit | edit source]

A newspaper, or online, feature article is composed of the following:

- a lede,

- topic sentence,

- a body, and an

- ending.[16]

The ratio of each of these may depend on the audience. In an inverted pyramid style the ratios are about 5:3:2 for lead (including topic sentence), body, and ending.

There is also what’s called a “news-peg” or “hook”, something that will interest a reader, usually the first sentence or the title.

The following elements should be present: What, When, Where, Why, Who, and How. Nearly all of these elements must appear somewhere in the story.

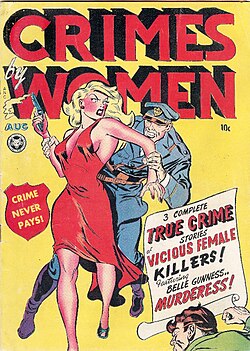

Crimes

[edit | edit source]

“Accounts of true crime have always been enormously popular among readers. The subgenre would seem to appeal to the highly educated as well as the barely educated, to women and men equally. The most famous chronicler of true crime trials in English history is the amateur criminologist William Roughead, a Scots lawyer who between 1889 and 1949 attended every murder trial of significance held in the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh, and wrote of them in essays published first in such journals as The Juridical Review and subsequently collected in best-selling books with such titles as Malice Domestic, The Evil That Men Do, What Is Your Verdict?, In Queer Street, Rogues Walk Here, Knave’s Looking Glass, Mainly Murder, Murder and More Murder, Nothing But Murder, and many more…. Roughead’s influence was enormous, and since his time “true crime” has become a crowded, flourishing field, though few writers of distinction have been drawn to it.”[17]

Debates

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Debates

Def. “a type of literary composition, taking the form of a discussion or disputation”[18] is called debate.

“On the other hand, it served to maintain the Moluccans’ challenge of and resistance to the dominant group’s definitions. These examples indicate that it is important to examine the actual use of the notion of ‘essentialism’ in argument and debate.”[19] Debate occurs in public meetings, academic institutions, and legislative assemblies.[20]

Debating is also carried out for educational and recreational purposes, usually associated with educational establishments and debating societies.[21]

Debating topics covered a broad spectrum of topics while the debating societies allowed participants from both genders and all social backgrounds, making them an excellent example of the enlarged public sphere of the Age of Enlightenment.[22] Debating societies were a phenomenon associated with the simultaneous rise of the public sphere,[23] a sphere of discussion separate from traditional authorities and accessible to all people that acted as a platform for criticism and the development of new ideas and philosophy.[24]

John Henley, a clergyman,[25] founded an Oratory in 1726 with the principal purpose of “reforming the manner in which such public presentations should be performed.”[26] He made extensive use of the print industry to advertise the events of his Oratory, making it an omnipresent part of the London public sphere. Henley was also instrumental in constructing the space of the debating club: he added two platforms to his room in the Newport district of London to allow for the staging of debates, and structured the entrances to allow for the collection of admission. These changes were further implemented when Henley moved his enterprise to Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The public was now willing to pay to be entertained, and Henley exploited this increasing commercialization of British society.[27] By the 1770s, debating societies were firmly established in London society.[28]

Dramas

[edit | edit source]

Def. “[a] composition, normally in prose, telling a story and intended to be represented by actors impersonating the characters and speaking the dialogue”[29] is called a drama.

“Through the sape, there develops what James Scott (1990), in his brilliant essay on resistance strategies in subcultures, calls “hidden transcripts”-a series of disguised messages and attitudes representing a hidden critique of the dominant group’s authority.”[30]

“Whatever multiplicity of expectations the public may have prior to their first experience with the drama, this system of signs tends to reduce them towards a sameness which conforms with the dominant group’s notion of social and artistic “validity” as incorporated into the theater design.”[31]

“On the one hand, a theatre seen as part of the unfolding social revolution involves theatre as a catalyst and a pusher in new directions which may not (in this case) represent the interests of an elite or dominant group.”[32]

Engineering

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Engineering

Def. the “application of [mathematics and the physical sciences][33] to the needs of humanity[34] and the development of technology”[33] is called engineering

On the right, as an example of engineering literature, is a cover image of the MuMETAL catalog where engineers, metal suppliers and fabricators have referred to mumetal as the industry standard.

Eroticas

[edit | edit source]

Def. literature “relating to or tending to arouse sexual desire or excitement”[35] is called erotic literature, or erotica.

On the left is a cover image from the new erotica e-book by Elizabeth Black called “PURR a Puss ‘n Boots Twisted Tale”.

“Here, for a fleeting moment (or occasionally even an entire evening), the existing social/sexual/economic power arrangements are challenged, where the client (who under “normal” circumstances has membership among the hegemonic, socially rewarding, dominant group of sexually conforming elites) temporarily crosses over the dichotomized chasm into the other world, and seeks temporary acceptance among those representing sexually challenging, alternative, erotic communities.”[36]

Essays

[edit | edit source]

Def. “[a] written composition of moderate length exploring a particular issue or subject”[37] is called an essay.

An essay is a piece of writing which is often written from an author’s personal point of view.

Fantases

[edit | edit source]

Def. a “literary genre generally dealing with themes of magic and [fictive][38] medieval technology”[39] is called fantasy.

Fictions

[edit | edit source]

Def. a “[l]iterary type using invented or imaginative writing, instead of real facts,[40] usually written as prose”[41] is called fiction.

Geography

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Geography

At the right is an allegorical painting in the Pinacoteca do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil, 1915.

It is one among many connected to the literature of the time preceded by a long and baroque heritage expressed even in the final years of the nineteenth century in various regions and in art and culture.

On the left is a form of geographic literature consisting of a geographic map showing the locations of Turkic peoples in and around Xinjiang, formerly East Turkestan.

History

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: History

Def. “[a] [written] record or narrative description of past events”[42] is called history.

On the right is an illustration of the “Hof van Beselare” in Flanders, Belgium, from the history book, Flandria Illustrata by Antoon Sanders.

Horrors

[edit | edit source]

Def. a “genre of fiction, meant to evoke a feeling of fear and suspense”[43] is called horror.

The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror specifically and exclusively focuses on and publishes current horror fictional literature.

“And like non-disabled women, they have a darker side; they are evil, depraved. They function as symbolic scapegoats for the dominant group, and hence the latter may feel horror and disgust and avert their eyes-or stare.”[44]

Humanities

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Humanities

On the right is a graph of Digital Humanities Twitter users with 1,434 nodes and 137,061 directed edges that each symbolize a user following another user.

Humor

[edit | edit source]

Def. the “quality of being amusing, comical, funny”[45] is called humor, or humour.

Intellects

[edit | edit source]

Def. “the faculty of thinking, judging, abstract reasoning, and conceptual understanding;[46] the cognitive faculty”[47] is called an intellect.

Laws

[edit | edit source]

Def. “[a] written or understood rule that concerns behaviors and the appropriate consequences thereof”[48] is called law.

Literary history

[edit | edit source]

“To justify the existence and the methods of literary history is entirely superfluous nowadays, and it is no less superfluous to dwell upon the differences and likenesses between it and literary criticism. Our common sense tells us, if we do away with prejudices and futile scholarly discussions, that literary history, working in its own field, is trying neither to replace nor to oppose literary criticism. Literary history thinks that it can help literary criticism; can clear a path for it; can lighten its task of understanding, judging, and classifying literary works and the great movements of human thought. It offers its services as a devoted auxiliary, modest and self-effacing. It has no imperialistic designs: it covers enough territory already to have no need to encroach on that of a neighbor. It prepares the material for the critic but puts no restrictions on the way [she] should use it. If he has faith in impressionistic criticism, if [she] believes that the literary critic should surrender himself to the emotion produced by the book [she] is studying and then should express this emotion with precision and delicacy, he is free to do so. Literary history asks [her] only to base his personal reaction on facts that have been historically verified, to define [her] position clearly, and, when communicating a purely personal reaction to the public, not to believe or to make others believe that he is giving any added information about the work or its writer. “Impressionism”, says Lanson, “is the only method that puts us in touch with beauty. Let us, then, use it for this purpose, frankly, but let us limit it to this, rigorously. To distinguish knowing from felling, what we may know from what we should feel; to avoid feeling when we can know, and thinking that we know when we feel: to this, it seems to me, the scientific method of literary history can be reduced.”1“[49]

Sweden

[edit | edit source]

The Rök runestone is considered the first piece of written Swedish literature and thus it marks the beginning of the history of Swedish literature.[50][51]

It was proposed that the inscription has nothing at all to do with the recording of heroic sagas and that it contains riddles which refer only to the making of the stone itself.[52][53]

The Rök runestone inscription is not connected to heroic deeds in war. Instead it deals with the conflict between light and darkness, warmth and cold, life and death.[54]

“The Rök runestone from central middle Sweden, [is] dated to around 800 CE […] Combining perspectives and findings from semiotics, philology, archaeology, and history of religion, the study presents a completely new interpretation which follows a unified theme, showing how the monument can be understood in the socio-cultural and religious context of early Viking Age Scandinavia. The inscription consists, according to the proposed interpretation, of nine enigmatic questions. Five of the questions concern the sun, and four of them, it is argued, ask about issues related to the god Odin. A central finding is that there are relevant parallels to the inscription in early Scandinavian poetry, especially in the Eddic poem Vafþrúðnismál.”[54]

Mysteries

[edit | edit source]

Def. a “suspenseful, sensational genre of story, book, play or film”[55], such as a “detective story, mystery novel, whodunit, crime fiction”, is called a thriller.

“The scripts for the series [I Love a Mystery] were usually themed towards the dark and supernatural, with perhaps the most famous, or infamous (depending on your point of view) scenario being “Temple of the Vampires,” which aroused a great deal of censorial comment when first broadcast as a twenty-episode serial from January 22 through February 16, 1940.”[56]

From the Mysteries of the Human Journey, Hegemony: “The persuasion of subordinates to accept the ideology of the dominant group by mutual accommodations that nevertheless preserve the rulers’ privileged position.”[57]

Narratives

[edit | edit source]

Def. “the systematic recitation of an event or series of events”[58] is called a narrative.

A narrative is a constructive format (as a work of speech, writing, song, film, television, video games, photography or theatre) that describes a sequence of non-fictional or fictional events.

Further, the word “story” may be used as a synonym of “narrative”, but can also be used to refer to the sequence of events described in a narrative. A narrative can also be told by a character within a larger narrative. An important part of narration is the narrative mode, the set of methods used to communicate the narrative through a process narration.

Natural sciences

[edit | edit source]

Def. a written work “studying phenomena or laws of the physical world”[59] is called natural science.

Novels

[edit | edit source]

“Their experience is encoded in the dominant culture as that of exotic Other, “foreigners,” as Ralph Connor revealingly titled his novel of immigration in the appropriate(d) discourse. This dominant group has framed the grounds for discussion of a “national literature.””[60]

“This point is crucial to understanding Donald’s internalized racism and the novel’s resistance to it: the dominant group obtains the consent of the subordinated group not by compulsion but by seduction.”[61]

“There is another distinction to be made in considering the Afro-American novel. Baker speaks of experiences in which the dominant group overtly discriminates against the black society and unabashedly allows distinctions that prove its superiority.”[62]

Philosophies

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Philosophy

Def. a written work “that seeks truth through reasoning rather than empiricism”[63] is called philosophy.

“The Tengrism tangraïsme or sometimes (in Mongolian: Тэнгэр шүтлэг, Tenger shütleg, worship (or religion) of heaven) was the major belief of Xiongnu and Xianbei which consisted of the Turkish population, Mongolian, Hungarian and Bulgarian in antiquity. It focuses around the divinity of the eternal sky Tengri (also transliterated Tangri, Tanrı, Tangra, etc.), and incorporates elements of shamanism, animism, totemism and ancestor worship.”[64][65][66][67] Translated using Google Translate.

That a text of this philosophy, or religion, probably existed is suggested by the stamp on the left used by Güyük Khan, in a letter of 1246.

Plays

[edit | edit source]

Def. “[a] literary composition, intended to be represented by actors impersonating the characters and speaking the dialogue”[68] or “a theatrical performance[69] featuring actors”[70] is called a play.

Poems

[edit | edit source]

Main resource: Poems

Def. a literary piece written in verse”[71] is called a poem.

Poetrys

[edit | edit source]

“Only those aspects of the minority culture that overlap the dominant culture are recognized by the dominant group.”[72]

“Their attitudes toward historical fact are complicated, but not because they are a muted group within a dominant group.”[73]

“It began with a rejection of the dominant group and a recognition of acceptance of blackness. In the enumeration and praising of black qualities, it reached its height in an “unfolding” common to both black American and black African poetry.”[74]

Romances

[edit | edit source]

The “popularity of old-fashioned romance novels featuring conventional and traditional gender roles seems to defy the stances of the modern-day women’s liberation movement.”[75]

A romance novel might be characterized as a “hyper-romantic, contrived and extremely unrealistic tales of handsome, manly heroes falling in love with virginal women, enduring a series of adventures, then inexorably ending in a happy resolution.”[75]

“Romance novels offer an escape from daily life with the belief that true love really exists.”[76]

“Romance novels [portrayed by the partial cover image on the right] are at once the most scorned and popular form of literature in the world, accounting for as much as 40% of total book sales in much of the world. The average romance reader (and writer) is female, ambitious, leads a very full and busy life, and has an above-average education and intelligence. The livelihood of some of the world’s most critically-acclaimed (mostly male) authors depends on the revenue base generated from the sale of the remarkably diverse genre called ‘romance’, written by and bought overwhelmingly by women.”[77]

Science fictions

[edit | edit source]

Def.’ “[f]iction in which advanced technology and/or science is a key element”[78] is called science fiction.

“Nerds also collect objects connected with knowledge (atlases and maps; mathematical and scientific equipment such as telescopes and slide rules; etc.), and are avid science fiction fans. … While they arguably represent a privileged and dominant group, many must reconcile this status with their experience of themselves as relatively powerless, or even subjugated, in their everyday lives.”[79]

“All the participants in a dominant culture do not necessarily belong to a dominant group. … This liquidation is the principal subject of Lovecraft’s opus, as I tried to show in “Entre le Fantastique et la Science-Fiction, Lovecraft,” Cahiers de l’Herne No. 12 (1969).”[80]

“When groups see themselves as opposed, competing for the same resources, subordinate groups may view the dominant group as cold, exploiting, cruel, and arrogant. … This is the case in the example at the end of this article, where-it is argued that “Aliens” in recent science fiction films are—among other things—figures for actual historical aliens who enter US borders, legally or illegally.”[81]

Leave a Reply